Thirty Metres of Murder: Alistair Carmichael Not In Court

“It’s quite unique to see a murder which you’re investigating on the silver screen. It’s just a shame the camera was pointing in the wrong direction.”- Kerstin Ekman, Thirty Metres of Murder Thanks to a combination of delayed flights and lost luggage on Sunday night after attending the European Law Institute conference in Vienna, I almost didn’t make it back to Glasgow in time to take part in STV’s live coverage of the trial of Alistair Carmichael’s election petition. Despite having been told it would be impossible to make my connecting flight home, I sprinted successfully through Brussels Airport, keen not to lose the chance to take part in the first live broadcast of a Scottish court case, only for Robert Black to politely remind me yesterday that the BBC had broadcast Abdelbaset al-Meghrai’s 2002 appeal against his conviction for the Lockerbie bombing.

So, no historic first there after all. (To the passenger beside me who had to put up with my coughing and general appearance of "about-to-expire mid-flight", sorry.) I did, however, feature in a BuzzFeed article entitled “Alistair Carmichael’s Court Hearing Was On Live TV And Everyone Found It Incredibly Dull”, so that’s something for my CV. And it was nice to meet Robert Brown and Lesley Riddoch, my fellow panellists for the first day of proceedings. Although, judging from Lesley’s Twitter feed during the broadcast, she may not have agreed.

Ouch.

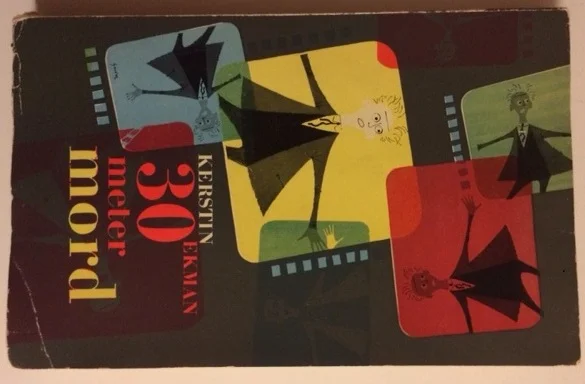

Anyway, my Sunday travel woes did give me plenty of time to read, when I started on a 1959 crime novel by the Swedish author Kerstin Ekman, entitled Thirty Metres of Murder. (Ekman, who largely abandoned detective fiction in the 1960s, is better known in the UK as a writer of literary fiction, and so has been ignored in the UK’s current fascination with “Nordic Noir”, despite her magnificent Blackwater once being voted the greatest Swedish crime novel of all time.)

At the outset of Thirty Metres of Murder, a young actor named Krister Hermansson is murdered during a film shoot, the camera catching his horror as he realises he is about to be shot, but not the identity of his killer. The police are excited about the possible value of the film footage, sending it by ferry to be developed and reopening the local cinema for a special screening, but quickly realise its limited value.

Not, perhaps, unlike the journalists who swiftly realised STV’s “Carmichael in Court” special (without Mr Carmichael) was not as exciting as they might have hoped.

I've often wondered why there's not more of a push to get TV cameras into court hearings but it turns out they're just incredibly boring.

— Jamie Ross (@JamieRoss7) September 7, 2015

To pursue the analogy with Ekman’s novel, did we see the death of Alistair Carmichael’s political career on the screen in front of us? Or were the cameras pointing in the wrong direction?

The legal issues involved in the case have already been discussed in various blogposts: most comprehensively by Andrew Tickell, but also by me and Heather Green. The proceedings of this week did not tell us a great deal which we did not already know (it was already clear that the petitioners were not seeking to run the "undue influence" argument which Dr Green had posited). The arguments were fleshed out considerably, with both parties having carried out extensive and impressive research, but the key issues in dispute remained as expected.

So what did we learn? A few points:

(1) Court cases do not make for great television. It is occasionally assumed that the barrier to greater televising of what happens in court rooms is a recalcitrant judiciary behind the times. But actually, a practice note on televising Scottish court cases was issued as far back as August 1992 by Lord Hope (then Lord President). The slow pace of development since then has been at least partly due to what the Carmichael case demonstrated – legal proceedings are often relatively dull and difficult to follow for those not already immersed in the details of a case. Lady Dorrian published a report early this year covering recording and broadcasting in court. That report recommends that there should still be no live transmission of proceedings involving witnesses, but it is possible that this might yet happen in Carmichael’s case – because of the imperative of allowing proceedings to be viewed in the constituency – in the unlikely event that Lady Paton and Lord Matthews were to consider it necessary that evidence be led in the election court.

(2) The petitioners have an arguable case, but “arguable” is not the same as “winning”. Jonathan Mitchell presented the petitioners case without difficulty, and his published note of argument is clear and easy to follow. The received wisdom surrounding the case, however, seemed to remain unchanged: Alistair Carmichael’s position is the stronger one. In proceedings with little intervention from the bench, one point stood out: Lord Matthews pressing Mr Mitchell on whether Alistair Carmichael’s leak was itself a political or a personal act. During the live coverage, that drew some criticism from one of the petitioners, who suggested that the bench did not understand that their case was not about the leak itself. But Lord Matthews clearly did recognise that. The point was more subtle. If the leak was political – and it certainly looks political – then is any statement about it not also of a political character? And if Alistair Carmichael’s denial of knowledge was a statement about his own political character, then the petitioners’ case fails in law. (There are other grounds on which their case could fail, but this was the one which took up most time in oral argument.)

As I understood him, Mr Mitchell sought support from the 1911 North Louth case here, where “betray[ing] Cabinet secrets to a foreign friend” was held up as an example of “personal delinquency”. But the analogy – which Mr Dunlop took issue with in his reply – is far from perfect. Mr Carmichael’s actions, whatever criticism might be made of them, were not traitorous.

(3) The law’s focusing effect can be frustrating. The relevant rules of electoral law mean that the petitioners must present their case in a very specific way. They must complain about Alistair Carmichael’s statement about his knowledge of the leak. They cannot complain about the leak itself. The petitioners must also show that this statement went to a matter of personal, not political, character. For better or worse, these are the rules of electoral law until Parliament decides otherwise. For those who support the petitioners, that is frustrating angels-on-pinheads stuff. If you have already decided that Carmichael should go (as the hashtag says) then the law is simply an impediment, not a guide to the correct result. Nor is it an attractive defence to say – as Andrew Tickell puts it – that “my lying was political, nothing personal”. (Not, of course, that Mr Carmichael does put it that way – “misstatement of awareness” is the phrase his legal team have preferred.)

The need to frame an argument by reference to rather narrow legal rules naturally leads some of Mr Carmichael’s opponents to conclude – to return to my tortured analogy – that the cameras were looking in the wrong direction; that the election court is not asking the questions which really matter to them. At the same time, it is clearly right that the power of the courts to void an election is narrowly constrained. During our discussion, Lesley Riddoch suggested to me that it would be a good thing for democracy if the courts were to overturn more election results. That seemed to me to be a surprising proposition at the time; it remains so. Voters ordinarily exact vengeance at the ballot box, not through the courts. Nothing in these proceedings tells us whether Mr Carmichael’s electorate would actually wish to do so, and – should he prevail in court – we cannot find out until an election takes place. But elections come rarely, particularly now that parliaments are fixed at a five-year term, and the wait for justice can be a frustratingly long one.

In this case, the wait will be rather shorter, but Lady Paton and Lord Matthews have some complex legal arguments to digest, and I expect to find out who murdered Krister Hermansson well before Mr Carmichael’s fate is determined.